Overview

My PhD and postdoctoral career has been focused on the role of filaments in the star formation process. This problem has risen to prominence as the Herschel Space Observatory showed that filamentary structures are ubiquitous in the interstellar medium, and importantly that most new stars are born within these filaments. It is currently unclear just what this means for star formation however as filament geometry changes how gravity, turbulence, magnetic fields and feedback act and interact with each other. My work tries to answer this question using numerical simulations, synthetic observations and real observations.

I am also highly interested in statistical techniques as well as testing and developing new analysis tools. Due to the large volume of data that is currently involved astrophysics, standardised, efficient, tested and often automated analysis tools are essential. So far I have developed tools to fit molecular line spectra, classify structure morphology and detect fragmentation length-scales.

Numerical simulations

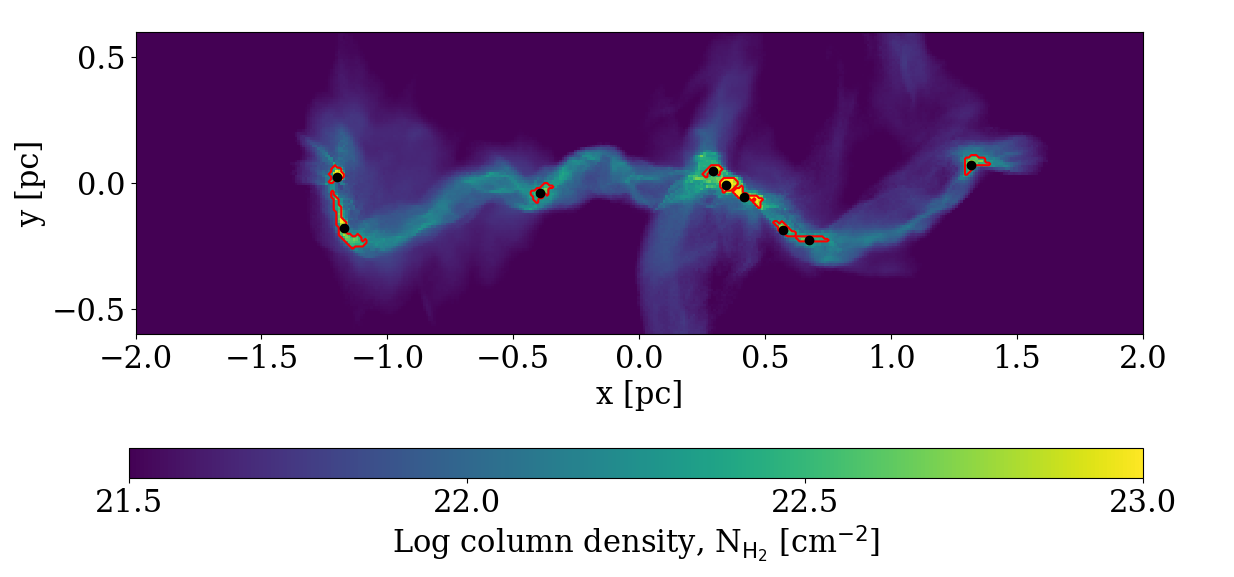

In my 2020 paper I investigated the hierarchical fragmentation of accreting, turbulent filaments. In my earlier work I discovered that internal turbulence leads to the formation of smaller sub-filaments within filaments, but what this means for the formation of cores was unclear. Here I found that cores form in two environments: (i) as isolated cores, or small chains of cores, on a single sub-filament, or (ii) as an ensemble of cores located at the junction of sub-filaments. I termed these isolated and hub cores, respectively. I showed that these core populations are statistically different from each other. Hub cores have a greater mean mass than isolated cores, and the mass distribution of hub cores is significantly wider than isolated cores. Interestingly, this fragmentation is reminiscent of parsec-scale hub-filament systems, showing that the combination of turbulence and gravity leads to similar fragmentation signatures on multiple scales, even within filaments.

In my 2020 paper I investigated the hierarchical fragmentation of accreting, turbulent filaments. In my earlier work I discovered that internal turbulence leads to the formation of smaller sub-filaments within filaments, but what this means for the formation of cores was unclear. Here I found that cores form in two environments: (i) as isolated cores, or small chains of cores, on a single sub-filament, or (ii) as an ensemble of cores located at the junction of sub-filaments. I termed these isolated and hub cores, respectively. I showed that these core populations are statistically different from each other. Hub cores have a greater mean mass than isolated cores, and the mass distribution of hub cores is significantly wider than isolated cores. Interestingly, this fragmentation is reminiscent of parsec-scale hub-filament systems, showing that the combination of turbulence and gravity leads to similar fragmentation signatures on multiple scales, even within filaments.

I also applied my FragMent module to study the fragmentation pattern of the filament into cores. I found that the fact that fragmentation proceeds through sub-filaments suggests that there exists no characteristic fragmentation length-scale between cores. This is in opposition to earlier theoretical works studying fibre-less filaments which suggest a strong tendency towards the formation of quasi-periodically spaced cores, but in better agreement with observations.

In my 2017 paper I presented simulations building upon my earlier work and investigated the effects of turbulence on the fragmentation of filaments. I showed that filaments that experience a weakly turbulent accretion flow fragment in a two-tier hierarchical fashion, similar to the fragmentation pattern seen in the Orion Integral Shaped Filament. Increasing the energy in the turbulent velocity field results in more sub-structure within the filaments, and one sees a shift from gravity-dominated fragmentation to turbulence-dominated fragmentation. The sub-structure formed in the filaments is elongated and roughly parallel to the longitudinal axis of the filament, i,e, sub-filaments. I showed that the formation of these sub-filaments structures is linked to the vorticity of the velocity field inside the filament, driven by the accretion. I also noted that the supercritical filaments that contain sub-filaments do not collapse radially, a possible solution to the problem of wide supercritical filaments.

In my 2017 paper I presented simulations building upon my earlier work and investigated the effects of turbulence on the fragmentation of filaments. I showed that filaments that experience a weakly turbulent accretion flow fragment in a two-tier hierarchical fashion, similar to the fragmentation pattern seen in the Orion Integral Shaped Filament. Increasing the energy in the turbulent velocity field results in more sub-structure within the filaments, and one sees a shift from gravity-dominated fragmentation to turbulence-dominated fragmentation. The sub-structure formed in the filaments is elongated and roughly parallel to the longitudinal axis of the filament, i,e, sub-filaments. I showed that the formation of these sub-filaments structures is linked to the vorticity of the velocity field inside the filament, driven by the accretion. I also noted that the supercritical filaments that contain sub-filaments do not collapse radially, a possible solution to the problem of wide supercritical filaments.

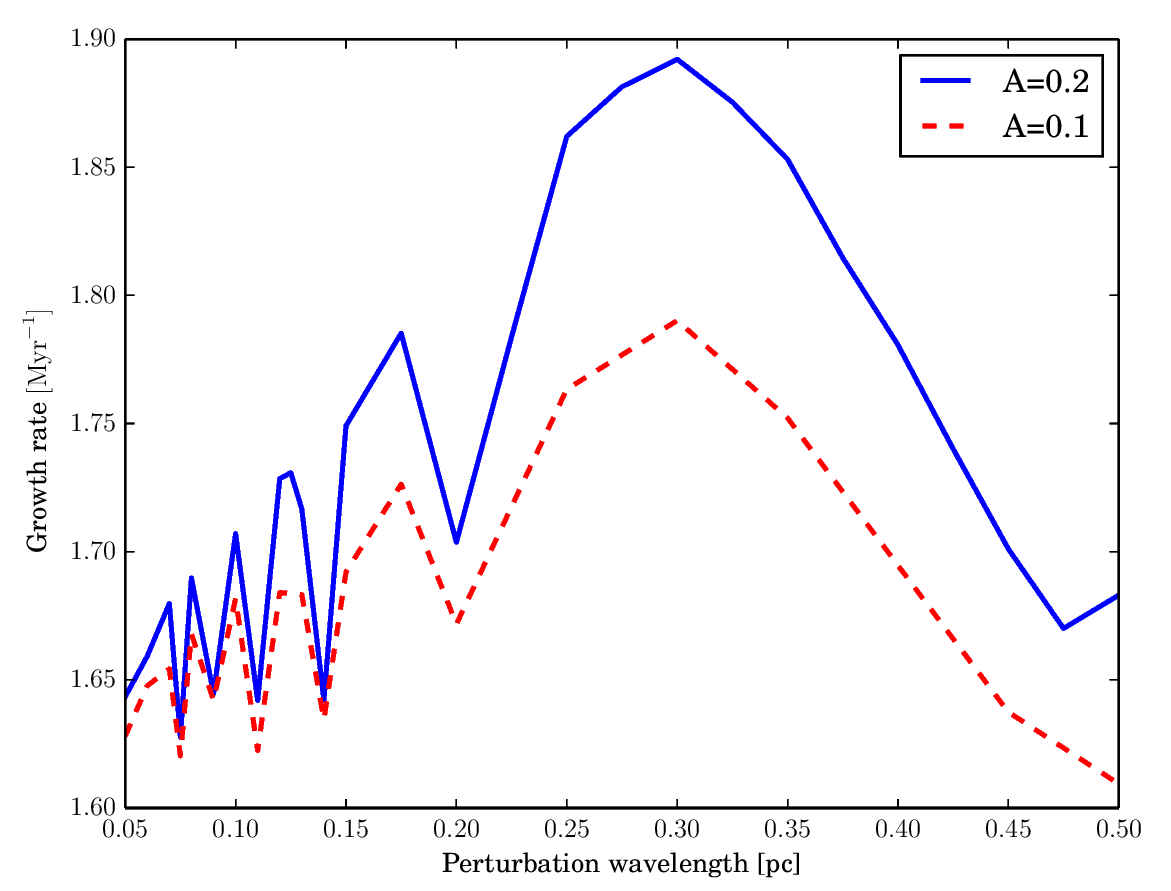

In my 2016 paper I investigated the growth of perturbations in infinitely long filaments as they form and grow by accretion. The growth of these perturbations lead to filament fragmentation and the formation of cores. Most previous work on this subject was confined to the growth and fragmentation of equilibrium filaments and found that there exists a characteristic fragmentation scale which is roughly four times the filament's diameter. My results showed a more complicated dispersion relation with a series of peaks linking perturbation wavelength and growth rate. These are due to gravo-acoustic oscillations along the longitudinal axis during the sub-critical phase of growth. The positions of the peaks in growth rate have a strong dependence on both the mass accretion rate onto the filament and the temperature of the gas. When seeded with a multiwavelength density power spectrum, I showed that there exists a clear preferred core separation equal to the largest peak in the dispersion relation.

In my 2016 paper I investigated the growth of perturbations in infinitely long filaments as they form and grow by accretion. The growth of these perturbations lead to filament fragmentation and the formation of cores. Most previous work on this subject was confined to the growth and fragmentation of equilibrium filaments and found that there exists a characteristic fragmentation scale which is roughly four times the filament's diameter. My results showed a more complicated dispersion relation with a series of peaks linking perturbation wavelength and growth rate. These are due to gravo-acoustic oscillations along the longitudinal axis during the sub-critical phase of growth. The positions of the peaks in growth rate have a strong dependence on both the mass accretion rate onto the filament and the temperature of the gas. When seeded with a multiwavelength density power spectrum, I showed that there exists a clear preferred core separation equal to the largest peak in the dispersion relation.

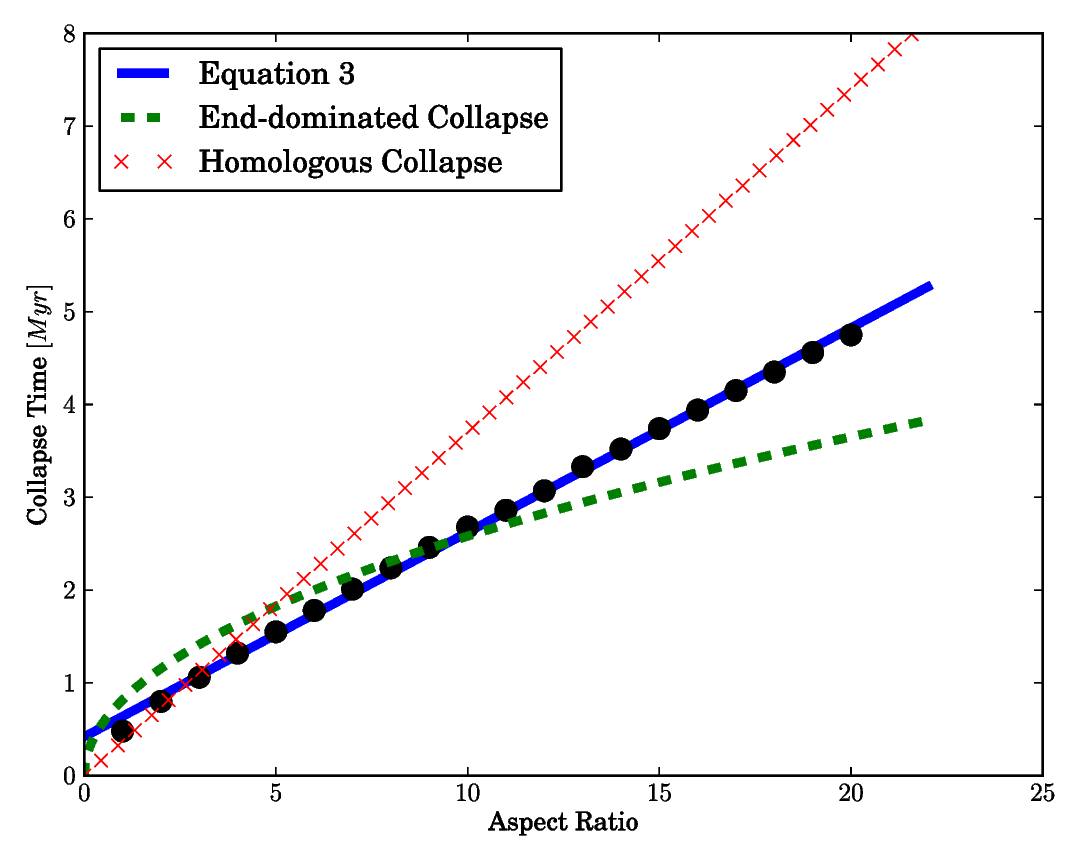

In my 2015 paper I investigated the longitudinal collapse time-scales of filaments; these time-scales are important because they determine the time available for a filament to fragment into cores. Pon et al. (2012) considered the global dynamics of filaments analytically and concluded that short filaments (with aspect ratios less than 5) collapse along the z-axis more-or-less homologously; in contrast, longer filaments (with aspect ratios greater than 5) undergo end-dominated collapse, i.e. two dense clumps form at the ends of the filament and converge on the centre sweeping up mass as they go. My simulations did not corroborate these predictions. First, the collapse is always end-dominated. Secondly, the collapse time satisfies a single equation of linear form which for large aspect ratios is much longer than the Pon et al. prediction. Thirdly, before being swept up, the gas immediately ahead of an end-clump is actually accelerated outwards by the gravitational attraction of the approaching clump, resulting in a significant ram pressure. For high aspect ratio filaments, the end-clumps approach an asymptotic inward speed, due to the fact that they are doing work both accelerating and compressing the gas they sweep up.This outward acceleration and its consequences was neglected by previous works.

In my 2015 paper I investigated the longitudinal collapse time-scales of filaments; these time-scales are important because they determine the time available for a filament to fragment into cores. Pon et al. (2012) considered the global dynamics of filaments analytically and concluded that short filaments (with aspect ratios less than 5) collapse along the z-axis more-or-less homologously; in contrast, longer filaments (with aspect ratios greater than 5) undergo end-dominated collapse, i.e. two dense clumps form at the ends of the filament and converge on the centre sweeping up mass as they go. My simulations did not corroborate these predictions. First, the collapse is always end-dominated. Secondly, the collapse time satisfies a single equation of linear form which for large aspect ratios is much longer than the Pon et al. prediction. Thirdly, before being swept up, the gas immediately ahead of an end-clump is actually accelerated outwards by the gravitational attraction of the approaching clump, resulting in a significant ram pressure. For high aspect ratio filaments, the end-clumps approach an asymptotic inward speed, due to the fact that they are doing work both accelerating and compressing the gas they sweep up.This outward acceleration and its consequences was neglected by previous works.

Synthetic observations

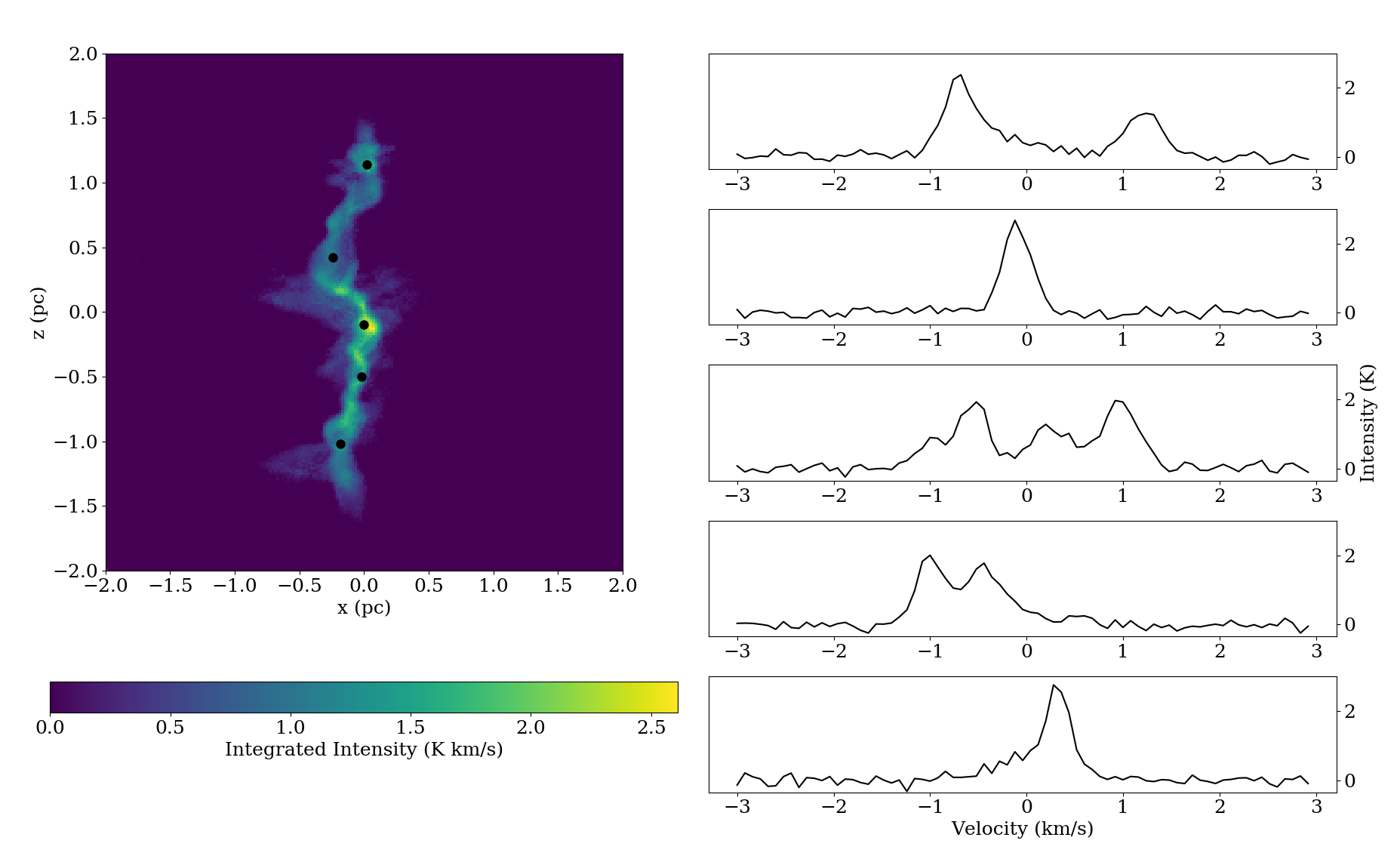

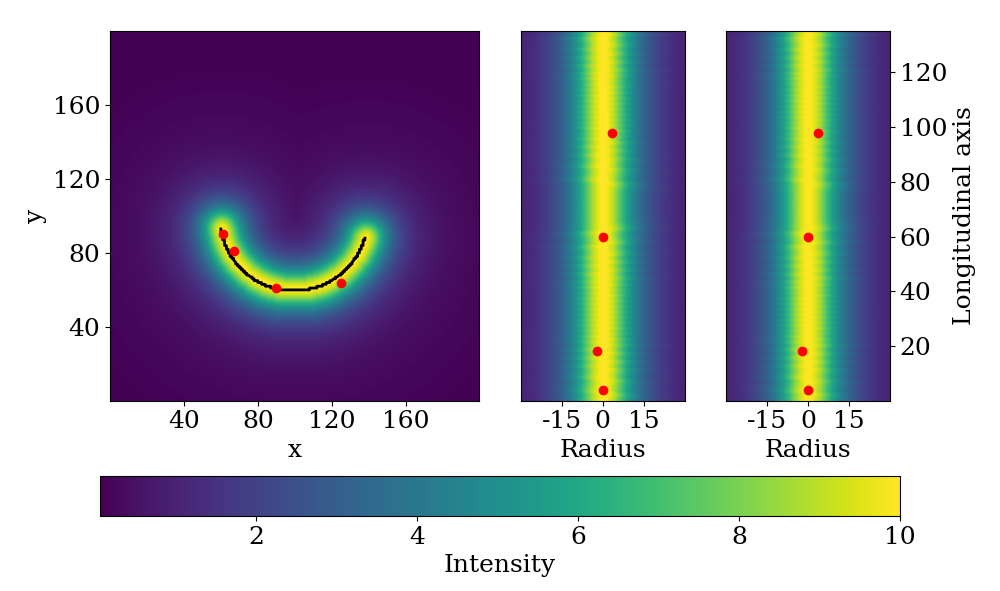

In my 2018 paper I presented synthetic observations of simulations similar to my 2017 models. Recent observations had shown that filaments contain inside them velocity coherent structures termed fibres. In this work I showed that fibres traced in position-position-velocity space are not guaranteed to be real coherent structures in position-position-position space. Rather, these fibres are kinematic artefacts of the accretion-driven turbulence which forms the real sub-filament structures seen in position-position-position space. Thus I showed that one should treat with caution interpretations of fibres as building-blocks of star formation. It is also in this paper that I presented my BTS code for fully-automated spectral fitting.

In my 2018 paper I presented synthetic observations of simulations similar to my 2017 models. Recent observations had shown that filaments contain inside them velocity coherent structures termed fibres. In this work I showed that fibres traced in position-position-velocity space are not guaranteed to be real coherent structures in position-position-position space. Rather, these fibres are kinematic artefacts of the accretion-driven turbulence which forms the real sub-filament structures seen in position-position-position space. Thus I showed that one should treat with caution interpretations of fibres as building-blocks of star formation. It is also in this paper that I presented my BTS code for fully-automated spectral fitting.

Analysis tools

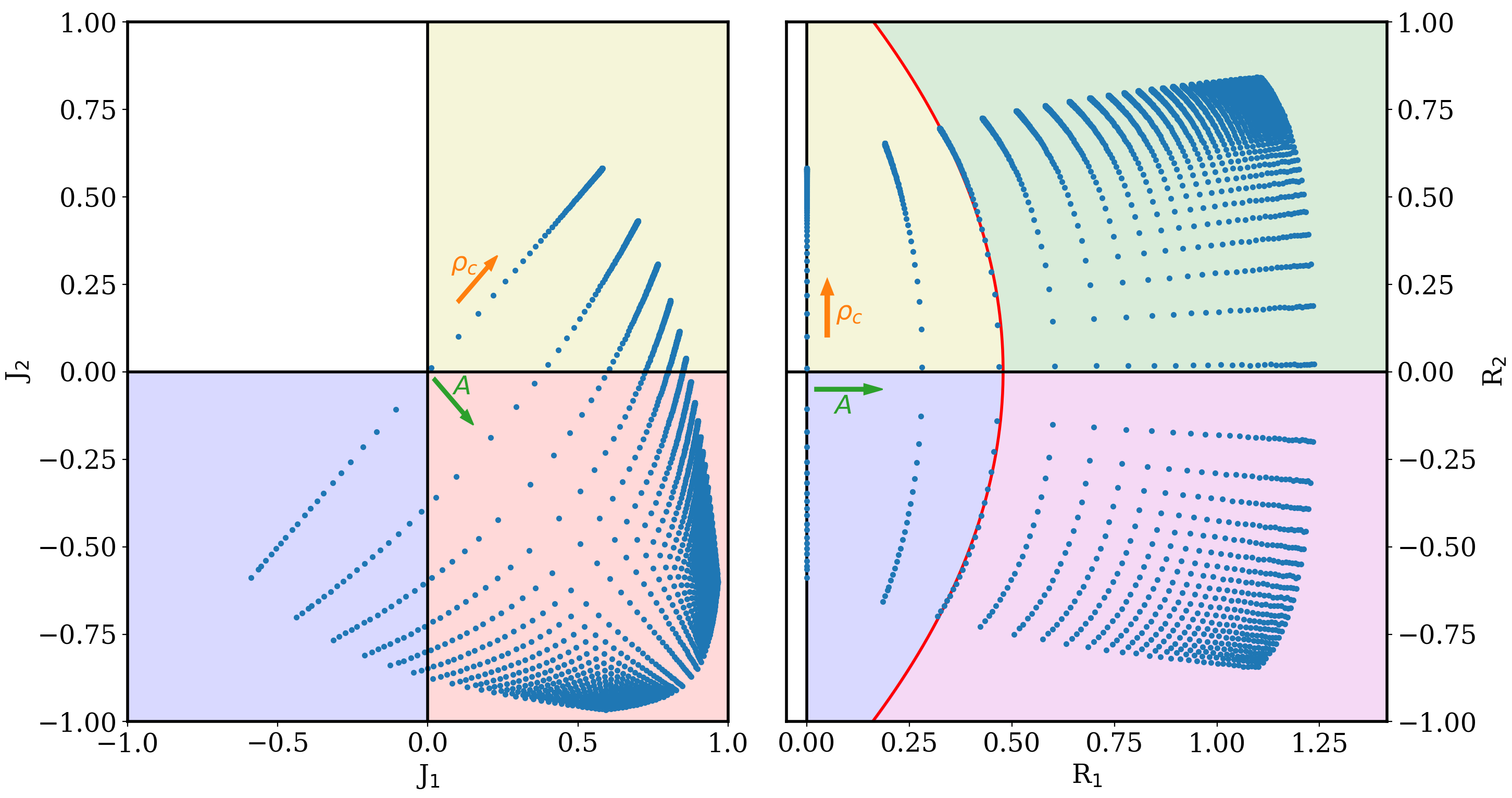

In my 2022 paper I presented the structure classification module RJ-plots. The large data sets resulting from observational surveys and state-of-the-art simulations studying hierarchical structures means that identification and classification must be done in an automated fashion to be efficient. RJ-plots allows clear distinctions between quasi-circular/elongated structures and centrally over/under-dense structures. I used the recent morphological SEDIGISM catalogue of Neralwar et al. (2022) to show the improvement in classification resulting from RJ-plots, especially for ring-like and concentrated cloud types. I also found a strong correlation between the central concentration of a structure and its star formation efficiency and dense gas fraction, as well as a lack of correlation with elongation. Furthermore, I used the accreting filament simulations from my 2020 paper to highlight a multi-scale application of RJ-plots, finding that while spherical structures become more common at smaller scales they are never the dominant structure down to r∼0.03 pc.

In my 2022 paper I presented the structure classification module RJ-plots. The large data sets resulting from observational surveys and state-of-the-art simulations studying hierarchical structures means that identification and classification must be done in an automated fashion to be efficient. RJ-plots allows clear distinctions between quasi-circular/elongated structures and centrally over/under-dense structures. I used the recent morphological SEDIGISM catalogue of Neralwar et al. (2022) to show the improvement in classification resulting from RJ-plots, especially for ring-like and concentrated cloud types. I also found a strong correlation between the central concentration of a structure and its star formation efficiency and dense gas fraction, as well as a lack of correlation with elongation. Furthermore, I used the accreting filament simulations from my 2020 paper to highlight a multi-scale application of RJ-plots, finding that while spherical structures become more common at smaller scales they are never the dominant structure down to r∼0.03 pc.

In my 2019 paper I presented my fragmentation module FragMent. Many models of filament fragmentation suggest that fragmentation characteristic scales should occur but no one knew which techniques were best at detecting them and how many cores would be necessary. I compiled a number of fragmentation analysis techniques and applied them to filaments, testing their sensitivity to characteristic scales. I also developed null hypothesis tests which should be used when judging the statistical significance of any suspected characteristic scales. From these I presented the best practice for investigating filament fragmentation: that a combination of the nearest neighbour separation, minimum spanning tree and two point correlation techniques should be used to detect characteristic scales; then a null hypothesis should be used to test the significance of the detection; and if the null is rejected one may decide if the observed fragmentation is best described by single-tier or two-tier fragmentation, using either Akaike's information criterion or the Bayes factor.

In my 2019 paper I presented my fragmentation module FragMent. Many models of filament fragmentation suggest that fragmentation characteristic scales should occur but no one knew which techniques were best at detecting them and how many cores would be necessary. I compiled a number of fragmentation analysis techniques and applied them to filaments, testing their sensitivity to characteristic scales. I also developed null hypothesis tests which should be used when judging the statistical significance of any suspected characteristic scales. From these I presented the best practice for investigating filament fragmentation: that a combination of the nearest neighbour separation, minimum spanning tree and two point correlation techniques should be used to detect characteristic scales; then a null hypothesis should be used to test the significance of the detection; and if the null is rejected one may decide if the observed fragmentation is best described by single-tier or two-tier fragmentation, using either Akaike's information criterion or the Bayes factor.

Observations

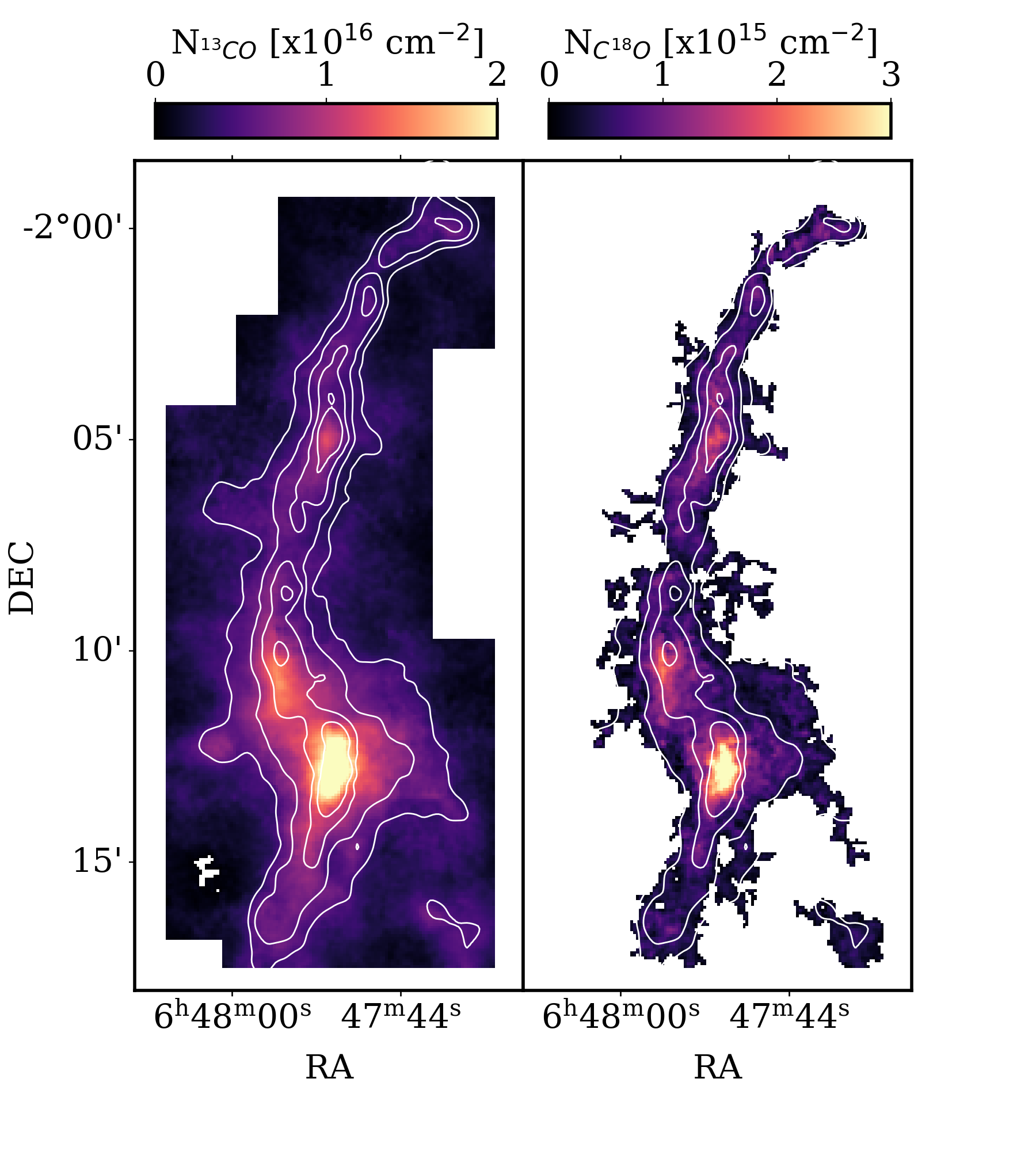

In my 2024 paper I presented an analysis of the outer Galaxy giant molecular filament (GMF) G214.5-1.8 (G214.5) using IRAM 30m data of 12CO, 13CO and C18O. I found that the 12CO (1-0) and (2-1) derived excitation temperatures are near identical and are very low, with a median of 8.2 K, showing that the gas is extremely cold across the whole cloud; this matches the low dust temperatures found in my 2023 work on G214.5. Investigating the abundance of 13CO across G214.5, I found that there is a significantly lower abundance along the entire 13 pc spine of the filament, extending out to a radius of ∼0.8 pc, corresponding to Av > 2 mag and Tdust < 13.5 K (as shown in the above figure). Due to this, I attribute the decrease in abundance to CO freeze-out, making G214.5 the largest scale example of freeze-out yet. I constructed an axisymmetric model of G214.5's 13CO volume density considering freeze-out and found that to reproduce the observed profile significant depletion is required beginning at low volume densities, n ∼ 2000 cm-3. Freeze-out at this low number density is possible only if the cosmic-ray ionisation rate is ∼ 1.9 × 10-18 s-1, an order of magnitude below the typical value. Using timescale arguments, I posited that such a low ionisation rate may lead to ambipolar diffusion being an important physical process along G214.5's entire spine. With these results in mind, I suggest that if low cosmic-ray ionisation rates are more common in the outer Galaxy, cloud-scale CO freeze-out occurring at low column and number densities may also be more prevalent, having consequences for CO observations and their interpretation in such regions.

In my 2024 paper I presented an analysis of the outer Galaxy giant molecular filament (GMF) G214.5-1.8 (G214.5) using IRAM 30m data of 12CO, 13CO and C18O. I found that the 12CO (1-0) and (2-1) derived excitation temperatures are near identical and are very low, with a median of 8.2 K, showing that the gas is extremely cold across the whole cloud; this matches the low dust temperatures found in my 2023 work on G214.5. Investigating the abundance of 13CO across G214.5, I found that there is a significantly lower abundance along the entire 13 pc spine of the filament, extending out to a radius of ∼0.8 pc, corresponding to Av > 2 mag and Tdust < 13.5 K (as shown in the above figure). Due to this, I attribute the decrease in abundance to CO freeze-out, making G214.5 the largest scale example of freeze-out yet. I constructed an axisymmetric model of G214.5's 13CO volume density considering freeze-out and found that to reproduce the observed profile significant depletion is required beginning at low volume densities, n ∼ 2000 cm-3. Freeze-out at this low number density is possible only if the cosmic-ray ionisation rate is ∼ 1.9 × 10-18 s-1, an order of magnitude below the typical value. Using timescale arguments, I posited that such a low ionisation rate may lead to ambipolar diffusion being an important physical process along G214.5's entire spine. With these results in mind, I suggest that if low cosmic-ray ionisation rates are more common in the outer Galaxy, cloud-scale CO freeze-out occurring at low column and number densities may also be more prevalent, having consequences for CO observations and their interpretation in such regions.

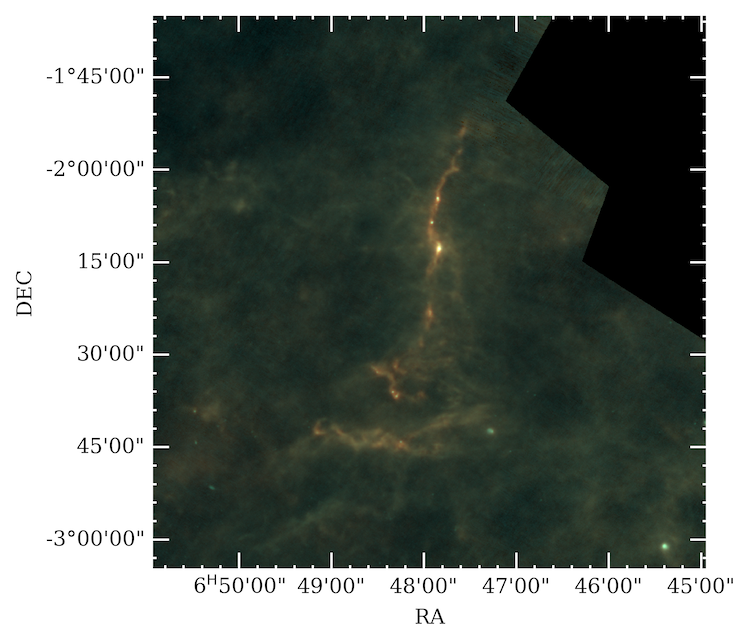

In my 2023 paper I presented an analysis of the outer Galaxy giant molecular filament (GMF) G214.5-1.8 (G214.5, seen above) using Herschel data. I found that G214.5 has a mass of ∼ 16,000 solar masses but hosts only 15 potentially protostellar 70 micron sources, making it highly quiescent compared to equally massive clouds such as Serpens and Mon R2. I showed that G214.5 has a unique morphology, consisting of a narrow `Main filament' running north-south and a perpendicular `Head' structure running east-west. I identified 33 distinct massive clumps from the column density maps, 8 of which are protostellar. However, the star formation activity is not evenly spread across G214.5 but rather predominantly located in the Main filament. Studying the Main filament in a manner similar to previous works, I found that G214.5 is most like a 'Bone' candidate GMF, highly elongated and massive, but it is colder and narrower than any such GMF. It also differs significantly due to its low fraction of high column density gas. Studying the radial profile, I discovered that G214.5 is highly asymmetric and resembles filaments which are known to be compressed externally. Considering its environment, I found that G214.5 is co-incident, spatially and kinematically, with a HI superbubble. A potential interaction between G214.5 and the superbubble may explain G214.5's morphology, asymmetry as well as the paucity of dense gas and star formation activity, highlighting the intersection of a bubble-driven interstellar medium paradigm with that of a filament paradigm for star formation.

In my 2023 paper I presented an analysis of the outer Galaxy giant molecular filament (GMF) G214.5-1.8 (G214.5, seen above) using Herschel data. I found that G214.5 has a mass of ∼ 16,000 solar masses but hosts only 15 potentially protostellar 70 micron sources, making it highly quiescent compared to equally massive clouds such as Serpens and Mon R2. I showed that G214.5 has a unique morphology, consisting of a narrow `Main filament' running north-south and a perpendicular `Head' structure running east-west. I identified 33 distinct massive clumps from the column density maps, 8 of which are protostellar. However, the star formation activity is not evenly spread across G214.5 but rather predominantly located in the Main filament. Studying the Main filament in a manner similar to previous works, I found that G214.5 is most like a 'Bone' candidate GMF, highly elongated and massive, but it is colder and narrower than any such GMF. It also differs significantly due to its low fraction of high column density gas. Studying the radial profile, I discovered that G214.5 is highly asymmetric and resembles filaments which are known to be compressed externally. Considering its environment, I found that G214.5 is co-incident, spatially and kinematically, with a HI superbubble. A potential interaction between G214.5 and the superbubble may explain G214.5's morphology, asymmetry as well as the paucity of dense gas and star formation activity, highlighting the intersection of a bubble-driven interstellar medium paradigm with that of a filament paradigm for star formation.